- Home

- Lone Theils

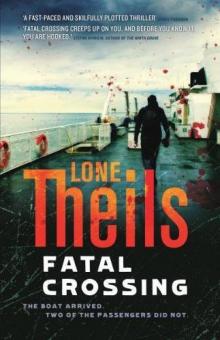

Fatal Crossing Page 20

Fatal Crossing Read online

Page 20

22

Back in London, while the taxi crawled slowly through the traffic, she stared at buildings and people in the streets rushing off to meetings about things that would mean nothing to people who had lost a daughter. Meetings about money, property and inanimate objects that ultimately didn’t matter.

She tried to clear her mind and let it work unencumbered while she vaguely registered that the driver had tuned his radio to BBC Radio 4, where a woman with an Indian accent was engaged in a passionate discussion with the presenter. ‘But it says so in the book. It says so in the book,’ she kept insisting.

The presenter tried his best to pour oil on troubled waters. ‘Mrs Singh. I don’t think we’re going to get anywhere, and we have other listeners waiting to give their opinion on what it's like for children in stepfamilies. But thank you for calling,’ he said, and got her effortlessly off the line before listing the number for listeners to call.

Something stirred at the edge of Nora's mind. Something about a book. Something written in a book.

Her thoughts travelled back as she tried to reconstruct events at the reception. She had signed the visitors’ log. A form in triplicate, which Foxy had left somewhere in the office. Nora replayed the movie in slow motion in her mind's eye as she took her pad out of her bag and made notes while her memories were still fresh.

She visualised Foxy's colleague, who had given too much away by telling her that Hix was visited only by his mother and sister. Something about the scene grated.

Her train of thought was interrupted when the cab driver slammed on the brakes to avoid hitting a young man listening to an iPod. The man's head was covered by a hoodie and he had crossed the road without looking. The driver rolled down his window and shouted at the top of his lungs: ‘Watch where you’re going, you moron!’

The only one on the street who didn’t react was the iPod guy who continued to sway to music only he could hear.

The taxi drove along Regent's Park with the radio still on. ‘But what about the government's family policy — has it failed?’ the presenter wondered out loud on the radio.

Family. Book. The two words collided in her brain and suddenly Nora realised what was wrong. She could barely wait to get home to check if she had remembered correctly. When the taxi pulled up outside her flat, she raced up the stairs without waiting for change or even a receipt to send to the Crayfish.

She found Murders of the Century on the floor. It had fallen from her bedside table and was lying half-hidden under a grubby T-shirt. She quickly looked up the chapter on young William Hickley and his mother.

Her memory was right: Something didn’t add up. The writer could be wrong, of course. Not done their research. It wouldn’t be the first time.

She found McCormey's number, called Dover police and introduced herself. To her surprise, she was put through to McCormey immediately.

‘Miss Sand. I think for you to call Spencer would be a really good idea. I know he's very keen to get hold of you,’ he said, without introducing himself.

‘Hmm,’ Nora grunted in what she hoped could be interpreted as a non-committal response.

‘I’m just telling you. Spencer is a man who usually gets what he wants. And he's not happy right now’

‘Neither am I,’ Nora retorted brazenly.

A short laugh escaped McCormey. ‘No, Spencer seems to have that effect on most people. But trust me — the work he's doing is very, very important. More important than him and his manners. Seriously, call him. Now.’

‘All right, all right, I will. But I’m not calling for advice on how to bond with Spencer. I was hoping you could help me with something. I’m trying to construct a profile of Hix. What he was like before he went to prison, that kind of thing, to get the full picture.’

‘Aha?’

‘And it got me thinking: during your investigation did you ever come across any family members, brothers or sisters or close friends possibly, whom I could contact to learn a bit more about what he was like as a child?’

A lengthy pause followed.

‘Eh, hello?’ Nora said to make sure that he hadn’t hung up.

‘Miss Sand. I’m not allowed to share information of that nature with the press, or indeed anyone else. I can’t tell you the name of a suspect's siblings. Even if that person was an only child, without any family or friends, I wouldn’t be able to tell you. Do you understand?’

‘Completely. Thank you,’ Nora said.

‘Was that all?’

‘There's just one more thing,’ she said, with fond memories of episodes of Columbo, which she had seen as a child, where the detective in his crumpled trench coat would always turn around in the doorway with one last and fatal question.

‘I know you can’t tell me anything, and this is a shot in the dark because I’m trying to follow a lead from Denmark. But have you ever come across a Danish man by the name Oluf Mikkelsen?’

McCormey seemed to think about it.

‘I can’t comment on individual investigations, of course. But I can tell you this much, that during my entire career as a police officer I’ve never come across that name. And I have a memory like an elephant,’ he then said.

23

The moment Nora had rung off, her voicemail beeped. Spencer had left four messages. She heaved a sigh and rang him back.

‘Miss Sand. You’re returning my call,’ he quipped.

‘Yes, so it seems,’ she replied.

A lengthy pause followed and Nora was in no hurry to fill it. Spencer was at fault here, not her.

‘Listen. I’m not someone who normally makes apologies,’ he began.

‘But?’

‘But nothing. That's just the way it is,’ he said bluntly, and yet Nora couldn’t help smiling down the phone. He reminded her of her brother David. A man on a mission.

‘I would like — we would like,’ he corrected himself, ‘to meet with you in here tomorrow morning at ten. We have important matters to discuss.’

‘Hmm. Not sure I can do tomorrow,’ she said.

‘Miss Sand. I’m asking you in the most tactful way I can. I’m not asking for myself, but on behalf of many other people. You need to come here for their sake,’ he said, pulling no punches.

Nora knew only too well that she had no real choice, if she were to have any hope of shaking off the images of Mr and Mrs Neuberg and the many missing girls.

When she had ended the call, she went back to her computer and found the pictures she had scanned from the newspaper coverage of Lulu's and Lisbeth's disappearance. She clicked until she found a group photo from Vestergården and enlarged it as much as she could, before zooming in on Oluf Mikkelsen.

The fact that he was one of three people out of a group of eight to go missing without a trace in the UK was unlikely to be a coincidence. If he had gone missing, that is. However, his fingerprint on the picture of Lisbeth and Lulu surely indicated some sort of connection.

Nora vaguely remembered a feature she had written a few years ago about British police launching a database for missing people, and a few Google clicks later, she had found it.

The National Missing Persons Register had been set up with a view to solving the mystery of the approximately twelve hundred unidentified bodies that at any given day lie forgotten in mortuaries across the UK. The earthly remains of people with no relatives to claim them and hold a funeral. Dead bodies with no names, life stories or the slightest evidence that someone once loved them.

Many of them were people who had succumbed to life in London and chosen to end it on the underground railway track, while others had drifted ashore along the coast, been found in burned-out houses or on park benches, their veins full of drugs. All they had in common was that they had left this life unnoticed by anyone, and that they had no names.

At the National Missing Persons Register all such findings were documented, photographed and collated from every police force in the country. With a heavy heart Nora clicked on the homepage, bracing

herself for pictures of frozen masks of what was once a living human being.

However, the homepage listed only a telephone number and an address you could visit if you had what they described as a ‘legitimate’ interest in getting access to the register's archives. It was in Walthamstow and it closed in exactly half an hour.

It was fair enough that they didn’t post pictures of dead people on the internet. There were already plenty of terrible things you could view by clicking, she thought.

She called the number and made an appointment for the following day, just after lunch.

24

Spencer was ready for her the moment she was sent up from reception, and he showed her into a meeting room where Irene and Millhouse were waiting with broad smiles and freshly sharpened pencils. At the centre of the table was a fruit bowl with delicious grapes, bananas and plums.

‘Miss Sand. How nice of you to join us,’ he said without a hint of irony.

Nora perched on the edge of her seat, reached for a banana, peeled it and wolfed it down in three bites. Breakfast.

‘Coffee?’ Millhouse offered, and she nodded, her mouth still full of banana.

He poured her a cup from the cafetière, while Spencer connected his laptop to an overhead projector and searched for what looked like a picture folder. Nora took a carton of whole milk and adjusted her coffee from black to light brown.

‘You did well yesterday,’ Irene said and winked at her.

‘I don’t think I made any difference,’ Nora said. ‘Because he didn’t tell us anything we didn’t already know, did he?’

Spencer cleared his throat. ‘Oh, he did. Perhaps not intentionally, but this is where we come into the picture. Where you come into the picture,’ he replied.

Nora took her first restorative sip and acknowledged yet again that not only was the coffee in Spencer's office at the higher end of what she had ever been served in a public institution, it was in a galaxy of its own compared to any coffee she had ever had anywhere in the UK.

She gawped at Millhouse. ‘What is this?’

He grinned from ear to ear. ‘Jamaican Blue Mountain. My father has a coffee shop in Soho. During my first week here at the Yard, I nearly went mental over the rubbish teabags and industrial mixes they had here, so I agreed with Spencer that I would take charge of the coffee,’ he explained.

Nora swirled the hot liquid around her mouth, tasting softness and a slightly burned aroma. Her animosity was washed away and she looked at Spencer with fresh eyes.

‘OK, how can I help you?’ she said, pulling out her notebook from her bag.

‘You can start by putting that notebook away,’ Spencer said acidly.

‘You never give up, do you?’

He shook his head with a hint of a smile and pressed a key on his computer. The grainy film of her meeting with Hickley appeared on the screen, and Nora couldn’t help shuddering at the sight of those eyes again. The camera was almost pointing straight at Hickley, and Nora concluded that it must have been wall-mounted diagonally behind her left shoulder. The volume was turned down and in one corner a timecode was running, displaying large white numbers.

‘I’ll let Irene start. She's a body language expert. In fact, she wrote her PhD based on TV recordings of Jeffrey Dahmer,’ Spencer said, referring to the notorious American serial killer who managed to murder seventeen boys and men before he was finally caught.

Irene leaned forward in readiness to review a recording she had presumably already gone over with a fine-tooth comb since yesterday, Nora imagined.

‘Please forward to four minutes and twenty seconds,’ she said.

Spencer did as she had asked.

‘Watch him now,’ Irene said, walking up to the white screen where the picture from Spencer's computer had been projected. She pointed with a green marker pen. ‘Here he's in total control of himself. He's leaning back. His gaze is steady, bordering on triumphant. Pay attention to his hands. They’re relaxed.’

Nora nodded. After all, she had been there herself.

‘Right, now try fast-forwarding about ten minutes.’

Spencer moved the mouse back and forth a bit, and stopped the recording near the end.

The change was noticeable and more obvious because there was no sound to distract them. Hickley was rocking restlessly back and forth on his seat. His hands clenching and unclenching. His eyes kept looking up sideways as people do when trying to access long-stored memories.

‘What are we talking about at that point?’ Nora blurted out.

Irene turned to Spencer. ‘Can we have the volume on, please?’

‘... been to Denmark?’

Nora's voice boomed across the room.

‘You’ve touched a nerve there,’ Spencer said softly. ‘There's something about Denmark. Something he’ll go a long way to hide.’

Nora nodded. ‘I had the same feeling myself when I was in there. But when you watch the recording, it becomes really obvious.’

Spencer smiled broadly. ‘I knew you’d understand.’

‘Hey, that still doesn’t mean it was all right of you to let me think I was going in there alone,’ Nora said, sounding more peevish than she had intended.

Millhouse poured her more coffee in an attempt to smooth her ruffled feathers. ‘What's important now is that we decide a strategy for our next move,’ he said.

Nora drank her coffee pensively. ‘I think I’ve blown my one chance. I don’t think he’ll slip up again. He lost control for a moment, but will he allow himself to do so again? Surely he’ll be even more guarded if I turn up a second time, won’t he?’ she said to no one in particular.

Spencer picked up on that. ‘We have to try again, and I must stress once more that you got further with him than anyone else.’

‘OK. Then let's just ignore for now that I have to go back and face an insane killer, and let's presume that I’m happy to do so in order to help solve the case. Seriously, what can I do to get him to talk? McCormey spent — how long was it — over ten years and never got anything out of him.’

Millhouse leaned forward. ‘But this is where you’re different, Nora,’ he said sincerely. ‘He's interested in you. He wants your approval.’

Nora's jaw dropped. ‘What do you base that on?’

‘On the fact that he tried very hard to impress you and build up a kind of rapport with you. He wanted you to call him Bill. With every other visitor, except family, he insists on being addressed as Mr Hix.’

Millhouse pulled a pile of papers stapled together out of the file. Nora could see it was a printout of their entire conversation. Millhouse had highlighted several passages in yellow.

‘You got a lot of things right. You weren’t submissive. You didn’t plead with him to answer your questions. And your decision to walk out bordered on genius,’ he said with admiration.

Nora stared blankly at him. ‘I just couldn’t stand being in the room with him any longer,’ she said.

Spencer pulled a face that could almost be taken to indicate regret. But only just, she thought.

‘You’ll have to get over that. You’ll be seeing a lot more of Hix,’ he said. ‘We’re trying to get a permanent permit in place. It’ll take a few days and then you can visit him whenever you want to.’

Nora shuddered at the thought. ‘But —’

Spencer interrupted her: ‘It's Saturday tomorrow, so the earliest I can have something ready is Wednesday. That's probably just as well. If you turn up any sooner, he’ll only get suspicious. And I need to talk to Cross, so he can prepare Hix. Get him in the right frame of mind, so to speak,’ he said.

‘And you think Cross will agree to it? Isn’t his first duty to his client?’ Nora asked.

‘Like I said, he owes me a favour. A big one,’ Spencer said, without elaborating any further.

Millhouse interjected: ‘And we have an extra ace up our sleeve. We can tempt him with the prospect of being transferred from a Category A prison. On ... how can I put it ... more

relaxed terms.’

Spencer took over again. ‘We have the weekend to work out a plan of action. I have some colleagues at Quantico and one in New Zealand whom I would like to consult. They have experience of how one goes about something like this.’

Nora chose her words with care. ‘I want to help as much as I can. However, I still have my day job

Spencer nodded. ‘I appreciate that. And I think that even at this stage I can promise you that we’re talking about a limited number of visits. But this might be our only chance to crack the case. I know that McCormey has great faith in you. You must have made a very favourable impression on him. For a journalist that's rare,’ he said.

Nora drank the rest of her coffee. Although it had grown cold, it left no trace of bitterness on her tongue.

‘Be ready for a briefing on Tuesday and possibly a meeting later next week. Deal?’ Spencer asked, and his eyes were grave.

She nodded and made to get up. ‘Right, then —’

And one last thing, Miss Sand. There was a reason why I told you to put back your notebook. Everything that happens in this room is confidential.’

‘But then how will I be able to —’

‘Confidential, until we agree otherwise.’

Nora sighed. All right, if that was how he wanted to play it. However, it also meant she was under no obligation to share information with him.

She said goodbye, walked to Green Park tube station and caught the Victoria line to Walthamstow.

25

She managed to walk past the Missing Persons Register twice before she finally spotted the small office in a basement under a pink hairdressing salon offering half-price Brazilian waxing.

Nora checked her watch. She was twenty minutes early and she toyed briefly with the idea of a spot of lunch at a pub called The Crown two doors down, but lost her appetite the moment she popped her head inside. It reeked of old chip oil and sour beer. Roxette's greatest hits poured effortlessly from the speakers, indicating that the new millennium had yet to reach this far-flung corner of Walthamstow.

Fatal Crossing

Fatal Crossing