- Home

- Lone Theils

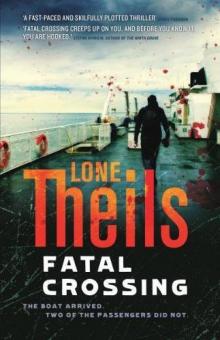

Fatal Crossing Page 8

Fatal Crossing Read online

Page 8

‘What happened to Jens?’ Nora was keen to know.

‘Not a lot. And Lisbeth dropped him like a hot brick. She let him know he was immature and that their fling in the back garden had been a mistake. Now he's married with two kids. Works for Vestas.’

‘Do you know anything about Lisbeth's or Lulu's families?’

Liselotte shook her head. ‘No details. I know that Lulu's dad lives somewhere in Copenhagen. Lisbeth's parents died when she was little, I believe. My dad might remember something. But then you’d better catch him before he gets too wasted,’ she said, checking her watch. ‘The Lamp opens in half an hour. That's your best bet. I think he lives in one of the holiday cottages with a woman called Jytte, but I don’t know exactly where. Sometimes it's best not to know too much.’ She smiled grimly.

‘Do you know what happened to the others who went on the trip?’

Liselotte shook her head again. ‘Nah. It all happened so fast once Social Services closed Vestergården. I mean, I know that one teacher died from cancer a few years later — and I think the other one moved to Australia. And I guess the kids were sent to other institutions. But God only knows where they are now. In jail, I’d guess, most of them. They were heading that way.’

Nora drank the rest of her coffee. It had grown cold and bitter. ‘Thanks for the brew,’ she said and made to get up.

‘Is this going in the paper?’ Liselotte wanted to know.

‘Well,’ Nora hesitated. ‘If I use it in an article, I promise to call you first and check the quotes. Is that all right?’

Liselotte nodded silently, returned to the turntable and chucked a lump of clay on to it.

‘You don’t mind seeing yourself out, do you?’

X

Nora treated herself to a quick trip to the North Sea before she went to the pub. She weaved her way through clusters of tourists, ice cream parlours and seaside shops hawking everything from plastic shovels to sarongs and water pistols. Once she had climbed the dunes, she felt serenity kick in.

You never knew just how much you missed the North Sea until you stood right in front of it, feeling infinitely small.

Along the English coast the Brits had their piers with fruit machines, bright lights and stalls selling candyfloss. Beaches where you could have a ten-minute donkey ride, and where children were so boisterous their parents were forced to scream and shout. Beaches where people dumped tons of rubbish every single day, and where it seemed only natural to munch your way through takeaway food and inflict your passion for techno on everybody else.

A Danish beach would be regarded as busy if you could make out one other person in the distance. Nora slipped off her sandals, carried them in her hands, and felt the icing-sugar sand between her toes.

So Lisbeth was no angel. Might she have been killed by someone she knew? Had she crossed the line once too often? Had she been a bitch to the wrong person? Was it possible that Bill Hix had absolutely nothing to do with her disappearance? But then what was her picture doing in his suitcase? And where did Lulu fit into all of this?

Nora turned around and wandered back to the town.

X

The pub's official name was The Lantern, but to the locals the maritime overtones were pretentious nonsense cooked up for tourists; in the local dialect it was only ever known as ‘The Lamp’.

A stale smell enveloped her the moment she opened the door. The room was dark, but behind the counter a middle-aged man was wringing out a dishcloth under the hot tap. He nodded to her before he started wiping the counter slowly and methodically. In the background, the popular 1970s musician John Mogensen expressed his musical opinion on living at number nine, Lonely Street.

Nora perched on one of the battered bar stools and ordered apple juice. The bartender nodded, found her a bottle of Rynkeby in the fridge, and opened it.

‘Ice?’

‘Yes, please.’

‘I’m guessing you’re not from around here,’ he said as he put a glass filled to the brim with ice cubes on the counter.

‘You can tell that simply because I ordered apple juice?’ Nora said in disbelief.

‘No. But trust me, none of the locals would waste twenty kroner on apple juice when you can buy two litres for the same money in Aldi in Hvide Sande,’ he explained. ‘Not that it's any of my business. But most people come here to drink,’ he said, gesturing towards the beer kegs.

‘I’m looking for Kurt Damtoft,’ she explained.

The bartender grunted. ‘Have you been talking to Liselotte?’

Nora nodded.

‘She's a good kid. It's a real shame that —’

The door was flung open with a crash. A slightly overweight woman in leopard leggings and a black, tight-fitting, low-cut top marched in. Her hair had been bleached, but her roots were showing, and the hoops dangling from her ears were big enough for a parrot to perch in each of them, without the wearer noticing.

‘Bugger me, I’m thirsty, Sjønne. A pint and a chaser, please,’ she demanded.

Sjønne was ahead of her. He had already lined up the pint and was busy pouring Nordsøolie into a shot glass. Glancing at Nora, he kept the bottle in mid-air.

‘So, how about it, Jytte, do you want me to pour Kurt's at the same time?’

‘Yes, go on. He’ll be here in a minute.’

Nora could see that Kurt wasn’t particularly drunk when he arrived, but also that he was hell-bent on remedying that situation as quickly as possible. It was essential to catch him now.

‘Are you Kurt Damtoft?’ she asked with no introduction.

He peered up at her suspiciously. ‘Who's asking?’

‘My name is Nora Sand. I’m writing about the girls from the England ferry.’

‘Bugger off. That old story. I don’t want to talk about it.’

‘Fair enough,’ Nora said, turning to the bartender. ‘I think Kurt would like another beer and a chaser. I’m buying.’

Kurt scowled for a moment. And Jytte,’ he then said.

And Jytte,’ Nora agreed.

The woman in Kurt Damtoft's life took her drinks and went to play on one of the fruit machines. He let out a deep and heartfelt sigh before he knocked back his Nordsøolie in one smooth movement, and looked across to Nora.

‘So, what do you want to know?’

One and a half hours and four rounds later, Kurt Damtoft reminded Nora more than anything of a tangled-up cassette tape. Some of the things he said made sense, while others sounded like incoherent muttering and meaningless noise.

Nora looked down at her notepad. She had listed the names of the other six youngsters who had been on the fatal journey.

Bjarke Helgaard

Oluf Mikkelsen

Erik Hostrup

Sonny Nielsen

Jeanette Viola Tobis

Anni Olsen

Below she had written ‘Viborg? Mikkelsgården?’ It was the name of the town and the care home Kurt Damtoft believed most of the young people would have been transferred to when Vestergården was closed.

‘To be honest with you, I couldn’t bear to be part of closing it down. Watching my life's work crumble in front of my eyes. In the end, I just walked away from it all — it got too much for me. Do you understand?’ he said in one of his more lucid moments.

Nora tried keeping him anchored in reality, but it was a losing battle. She realised now why Kurt Damtoft had never featured in the TV documentary about the girls.

‘Do you remember anything about Lisbeth's or Lulu's families? Where they were from?’

Kurt Damtoft turned to her and stared at her with glassy eyes.

‘My girls aren’t dead. They’ve just gone out for a while,’ he rambled.

‘Why would you think that?’

‘Because they sent me a postcard ... I think,’ he slurred.

‘Is that right? Do you still have it?’ Nora asked, unable to hide her scepticism.

‘I got bugger all left of anything,’ Kurt Damtoft said, turning towar

ds the fruit machine. ‘Jytte! I want go home now!’ he shouted over the music.

Nora took her leave politely, settled her not-inconsiderable bar bill and asked for a receipt, knowing full well that the chances of the Crayfish reimbursing her were minimal.

‘What happened to Vestergården?’ she asked the bartender while he sorted out her change.

He shrugged. ‘The place has been vacant for years. A few years ago there was talk of turning it into a kind of conference and holiday centre. Then the financial crisis happened. I don’t even know who owns it these days. The council, I guess.’

‘Where exactly is it?’

He wiped the counter again as if it was the most important job of the day. Took his time before he replied.

‘Lyngvej. Third road on your left when you drive towards Ringkøbing. It's some way into the plantation.’

Nora thanked him and left him a shiny twenty kroner coin by way of a tip.

X

As she got into the car, Big Ben chimed from the bottom of her handbag.

‘Yes, boss?’

‘How do you always know it's me?’ the Crayfish wanted to know.

‘Modern technology has come a long way in recent years,’ she said enigmatically.

‘Hmm. Am I getting my money's worth out of you?’

Nora outlined her efforts so far.

‘What happened to the English lead? Anything from Hickley's lawyer?’

‘Not yet. He isn’t meeting with his client until later this week.’

‘What about Hickley's old mother — is she still alive?’

‘Good point, I don’t know.’

‘Hmm. Call Emily in Research. She might be able to get you something on the other kids from Vestergården.’

Nora said goodbye and did as she was told.

Emily had started as an intern in the dawn of time, but had found working for Globalt infinitely more attractive than a job at a public library and had become a full-time employee after finishing her librarianship training. In addition to running the electronic newspaper archive, she researched everything from Swedish prostitution legislation to the number of nursery places in Roskilde council to the average wage in Indonesia — or any other bizarre question journalists might happen to ask.

‘Helgaard, maybe. Hostrup, possibly. Tobis, probably. Nielsen, Mikkelsen and Olsen — forget it. Their surnames are too common,’ she said. ‘I’ll call when I have something. Remind me of your mobile number, will you?’

Nora gave it to her, and headed for Ringkøbing.

X

She found Lyngvej easily. A narrow cart road led to a pine plantation, and the tall grass between the cart tracks revealed that this place no longer had daily or even weekly visitors.

The road bent and she pulled up in front of the house that had once been Vestergården. A main building that must have been the original farmhouse, and two typical 1970s concrete extensions, painted dark red in a failed attempt to match them to the main house. Two sacks of cement were lying in the yard. One had a hole in a corner and a little had spilled out. Abandoned scaffolding lay next to it.

Nora stopped her car and got out. In the silence that ensued she could hear the engine click as it cooled and a bird's furious squawk in the forest. The smell of resin, sea and heather lingered in the air. She held up her mobile to take some pictures and walked closer to the house. The greasy, salty air had obscured the windows. This was where Lisbeth and Lulu and the other teenagers had left one August day all those years ago. Full of dreams and hopes, and excited about their trip to London. A trip that would change the lives of all the broken souls who had ended up at Vestergården.

The flat where Kurt had lived with his family was in the main building. And the two extensions must have housed the boys and girls, respectively. Nora wandered around the main building and headed for a hill to get a better view of Vestergården.

The grass in the back garden was so tall that you would need a scythe if you were ever to turn it into a lawn again. Nora turned and looked back at the house; the window panes stared silently back at her. As she turned she sensed rather than saw it. A slight movement out of the corner of her eye. A glimpse of something darker than the rest of the window. She shook her head and dismissed the thought. But the next moment the darkness returned. There was someone inside the house. Was it inhabited after all? Nora looked around.

There was no sign of anyone. No cars, no bicycles. If someone had come here, it must have been on foot. She walked back, carefully approaching the house. Was that a face she had seen? Hidden behind the dark windows?

When she came closer, she could see she was looking through a kitchen window. She pushed her face right up to the glass and cupped her hands to shield against the sunlight. The kitchen sink was covered with clear plastic and on the kitchen table there was a plastic bucket with something that looked like dried paint. A coffee mug with a teaspoon sticking out of it was sitting next to it, and near the mug there was a large, rust-coloured splodge that looked like a handprint. There was another handprint on the once-white tiles on the wall by the sink. Was it blood? Nora narrowed her eyes and peered further into the kitchen. She tried wiping away the salty film with one hand, but succeeded only in smearing it across the glass.

She jumped when the crash of a door slamming rent the silence. Where had it come from? She started running to the other side of the house, but tripped and fell in the tall grass. When she got back on her feet, she heard the roar of a car engine. She raced back to the yard. The garage door had been opened and she just had time to see the back of a black 4x4 as it cornered the bend in the road. Her hands were shaking as she retrieved the car keys from her pocket and jumped into her car, but when she reached the main road, there was no sign of the black car anywhere in the flat landscape. It appeared to have vanished into thin air.

Nora tried to shake off the incident and looked up directions to Viborg on her mobile.

X

Her mobile rang an hour later. Nora pulled over and took Emily's call.

‘Tobis died from a drug overdose five years ago. Her body was found by a tourist at Copenhagen Central Railway Station.’

Nora pulled the list out of her handbag and crossed her out.

‘Helgaard, Bjarke. Now I can’t guarantee it's the same guy, but his name pops up in connection with several biker gang cases. He's the spokesman for a Chapter on Nørrebro. A beefcake on steroids, judging by the pictures. Hostrup. Now that was interesting. There's a Hostrup Gallery in Copenhagen. The owner is listed as E. Hostrup. Then there's a teacher from Kolding, also called E. Hostrup. And someone called E. Hostrup lives in Hedehusene, but currently is in prison for watching child porn on the internet.’

Bingo, Nora thought.

Now only Anni Olsen, Sonny Nielsen and Oluf Mikkelsen remained. Perhaps they would know more about them at Mikkelsgården.

‘Ah, yes about that. Mikkelsgården is still an institution for young people. The warden is called Jette Kvist. She's able to meet with you tomorrow morning at ten, but warns you in advance that she can’t or won’t discuss individual cases. No matter how ancient they are. I’ll text you the address,’ Emily said in her usual staccato style.

Nora managed one question before Emily hung up. ‘Please would you check something else for me?’

‘Yes. What is it?’

‘Vestergården. Lyngvej with a Ringkøbing postcode. Who owns it — any information from the Land Registry office?’

‘Give me five minutes.’

Nora took the chance to stretch her legs while she waited. She managed barely four minutes of exercise.

‘The local council owns it. Again. They bought it back for next to nothing from a construction company two years ago. That company had bought it from the council for almost twice that amount only the previous year. Clever council. The construction company, however, went bankrupt.’

‘And would you happen to know the name of the construction company?’

‘Funny, I h

ad a hunch you were going to ask. It was called Ferie-huset ApS. A private limited company now dissolved. However, directors included gallery owner Erik Hostrup. I mention it merely because I came across his name earlier.’

‘Emily, remind me why you’re not a journalist?’

‘Oh, it's too dull,’ she said and rang off.

Nora checked her rear-view mirror before rejoining the motorway, but slammed on the brakes when she spotted the black 4x4 again. It was driving steadily towards the layby where she was parked. And then it carried on.

She craned her neck trying to see the driver, but the windows were tinted and the registration plate covered in mud. She could just about make out the outline of the letter K and the number seven.

Not even Emily could work her magic with so little information. That is, if it even was the same car.

11

The name Mikkelsgården conjured up an image of the sort of thatched farm that ought to feature in a 1950s Danish family film starring a very young Ghita Nørby The reality was more like the film set for 1970s East German social realism. As she turned into the drive, she saw grey, badly maintained concrete that had started to crumble, and tiny windows that gave the building a menacing look.

‘All visitors must report to reception without exception,’ a bright yellow sign announced, the only source of colour in the grey landscape.

Nora checked her watch and strangled a yawn. It was five minutes to ten. She had had a rotten night's sleep at a hotel. She cursed the hotel tradition of tucking sheets and blankets in so tightly under the mattress that you either had to tear everything apart or accept sleeping like a butterfly skewered on a pin in a display cabinet.

She had fallen asleep during the late DR2 News and woken up around three in the morning with pins and needles in her legs from the stranglehold of the sheet. Once she had got out of bed in order to make it more comfortable, she found it practically impossible to get back to sleep.

Fatal Crossing

Fatal Crossing